|

By Will Nash '20

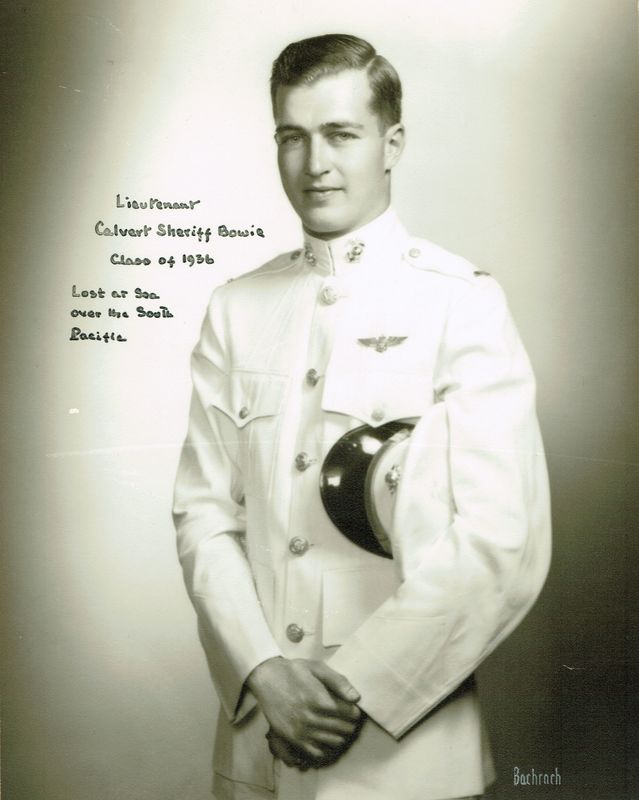

On August 6, 1945, a B-29 bomber called the Enola Gay dropped a uranium atomic bomb nicknamed “Fat Man” on the city of Hiroshima, Japan. Three days later, a plutonium atomic bomb nicknamed “Little Boy” was dropped on Nagasaki. As a combined result of the two bombs, 250,000 Japanese were killed, and many more were maimed, disfigured, or burned by the blast. The bombings were justified because the Japanese refused to listen the Allies’ repeated warnings regarding the atomic bomb, and because there was no feasible alternative to ending the war that would not result in massive Allied casualties. On July 26, 1945, the leaders of all the Allied powers met in Potsdam, Germany, and issued the Potsdam Declaration which called for Japan’s unconditional surrender. If Japan failed to comply, the Allies threatened Japan’s “prompt and utter destruction.” The day before the Potsdam Conference opened, the U.S. had successfully detonated the first atomic bomb in New Mexico, making that “destruction” feasible. The Japanese ignored this ultimatum. President Truman warned in a speech played over Japanese news stations that the Japanese “could expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth” if they did not accept the terms of the declaration. The Japanese ignored this threat as well. Japan was given ample time to surrender, and each time they rebuffed Allied demands. They continued to fight in the Pacific theater, taking the lives of many American soldiers. The U.S. therefore can hardly be blamed for following through on these threats in order to end a war that was becoming more and more costly both in terms of money and American lives. From the beginning, the U.S. was reluctant to drop the bombs. U.S. generals weighed all their options before deciding on the atomic bomb. A land invasion called Operation Olympic was planned for Kyushu, the southernmost Japanese island, but because Japan’s mountainous terrain provided few landing sites, the Japanese predicted where the Americans would land. The Japanese fortified Kyushu with 2.3 million soldiers backed by a civilian militia of a million men and women in what was to be an all-out defense of Japan. Japanese soldiers were prepared to fight to the last man in a war of attrition to force the U.S. to negotiate a peace treaty. A study commissioned by the Joint War Plans Committee estimated that Olympic would have resulted in anywhere between 25,000 and 46,000 American deaths. In a war in which the U.S. had already lost almost 300,000 men, these losses were unthinkable to U.S. generals. Another option was to continue the strategic bombing campaign the U.S. had embarked on in 1944 in which they firebombed major Japanese cities such as Tokyo to undermine Japanese morale. However, the campaign had been largely ineffectual, as the Japanese refused to be bombed into submission. A long-term blockade as well was not a feasible option because U.S. generals were facing much pressure back home to get American troops out of the Pacific theater. Therefore, the U.S. was left with no option but to use the bomb. Captain Calvert Sheriff Bowie US Marine Corps Reserves, O-010314 STA Class of 1936 February 13, 1918 - May 30, 1943 Lost at Sea Cal was never missing. Since he entered St. Albans in Form I in 1930, Calvert Sheriff Bowie held a strong place in the community by making his mark on the athletic fields. A football player and First Team Basketball and Baseball player, Cal’s classmates not only enjoyed watching him from the stands but also being in his company. “Cossy,” as they called him, was “likeable and even-tempered,” social and talkative with “genial nature and ready smile.” More than a St. Albans man, Cal was a St. Albans gentleman, a concept that would never fail him, or, rather, that he would never fail. After graduating St. Albans in 1936, he joined other gentlemen in the ΣΑΕ fraternity at Dartmouth, from which he graduated, in turn, in 1940. Returning to his hometown of Washington, D.C., Cal enrolled in Georgetown Law School. All that he had learned in the classroom at St. Albans and at Dartmouth had beckoned him to a successful year of law school, but what he had learned, and more importantly practiced, outside the classroom called him to leave his desk in the spring of 1941 to join Naval Aviation Training. Cal brought everything he had to his service, personally selected by the Aviation Arm of the USMC. But his notion of a gentleman, which he had always lived by, would soon become more than a code that governed free society; it would become the honorable yet costly way he defended free society. On May 14, 1943, Cal was a member of the Marine Torpedo Bombing Squadron over the Solomon Islands where he laid two direct hits on a Japanese cargo ship, despite horrible visibility. The ship became stranded on a nearby beach, all but destroyed. Days later, however, Cal would suffer the ultimate tragedy himself. On May 30, Cal went missing on a reconnaissance mission near Guadalcanal. No, Cal is still not missing. While his person itself was never found, Cal now holds a place among those who have paid the ultimate price. He has been awarded a Purple Heart Medal and an Air Medal, the latter of which came with citation from Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox. Perhaps an equally powerful token to Cal’s nobility, however, is the St. Albans scholarship his father established in his honor. A World-War-Two hero, Cal will always be a St. Albans gentleman and an example for those to come.

|

|