|

Story by Kevin Quigley '18 Usually, English class is very boring. Out teachers batter us with motifs, symbols, and theories that we definitely pay attention to so we can write our essays and be done with them. “What is the significance of the green light in The Great Gatsby?” “What does The Canterbury Tales tell us about medieval society?” “What does the color blue symbolize in The Glass Menagerie?” English classes seem to tell us that the only important thing in reading a novel is finding the meaning. Not the plot, not the setting, not the characters—only themes! And yes, finding the morals and themes of a work is the end result of reading a novel. However, this obsessive focus on theme prevents most of us from enjoying what we’re reading.

1 Comment

Story by Fred Horne '18 Amendment XVII The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State, elected by the people thereof, for six years; and each Senator shall have one vote . . . The Senate as established in Article I, Section 3 of the Constitution was a great bastion of federalism. Equal representation of every state and the election of Senators by state legislatures both ensured that the states remained the fundamental unit of American government. The election method especially ensured the states’ continued power, because Senators elected by state legislatures implicitly represented the state-based opinions and interests of those legislatures. At its heart, however, the provision that state legislatures elect Senators reflects the Framers’ elitism. They thought that the “cream of the crop,” to whom the people had already entrusted their state governments, were better informed and could choose better Senators than the people at large. The same presumption motivated the creation of the Electoral College, though it has long since lost any power to shape the states’ votes. This state-focused, elitist view did not survive the 19th century. Between 1792 to 1856, every state abolished property qualifications for white men to vote. Advances in transportation and communication tied the nation together, turning the focus of the people from their states to their nation. The era of Andrew Jackson saw the common man seize his full role in democracy, discrediting the elitist republic of Alexander Hamilton. The 14th amendment penalized the states for denying suffrage to any adult male citizens; the 15th forbade denial on the grounds of race or previous servitude.

The corruption of the Gilded Age only intensified this desire for popular democracy. By the late 19th century, corruption was so rampant in state legislatures that they were regularly bribed to elect rich industrialists to the Senate, making the Senate a “millionaires’ club” unresponsive to the people. Moreover, deadlock in state legislatures often resulted in no candidate being elected and the state’s Senate seats lying unoccupied for an entire session or more. In 1892, the People’s Party was formed to “restore the government of the Republic to the hands of the ‘plain people.’” It demanded direct election of the President, Vice President, and Senators, among other proposals intended to remove government from the hands of the wealthy elite. Although the party collapsed in 1896, the Democrats took up the torch of direct election in 1900 and joined the throngs who called for change. The states started moving toward direct election of Senators in response to these circumstances. Many states amended laws to allow the people to unofficially designate their preferred candidates, with 31 states introducing unofficial direct election by 1912. The House of Representatives, more closely attuned to the people, passed an amendment allowing for the direct election of Senators in 1894, 1898, 1900, and 1902, defeated each time in the Senate. Finally, the Senate bowed to the inevitable in 1912, and 17th amendment was ratified in 1913. This amendment caused a fundamental shift in the Senate. Direct election introduced candidates who sought the voters’ endorsement and so listened to the people, not simply the coin purse. Today it may seem like an obvious amendment, the sort of thing where we wonder why it took so long to pass but give it little note. In truth, the 17th was one of the more important moves toward democracy that our government has ever made. Story by Fred Horne '18 AMENDMENT XVI The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration. It is said that the only things certain in life are death and taxes. The ratification of the Sixteenth amendment in 1913 made “taxes” just a little more certain. It expanded Congress’s power to allow direct taxation of income. But the first income tax Congress levied was during the Civil War, long before the passage of the 16th. The constitutionality of the income tax was upheld in Springer v. United States in 1881, so why was the 16th necessary? The Court changed its mind.

Story by Zach Selassie '18

Story by Matthew Kellenberg '18 2017 has been a whirlwind of a year for online advertising. Youtube is under fire from the the Wall Street Journal for allowing advertisements on racist videos, Kendall Jenner brought the world together with a Pepsi, and famed mentor Tai Lopez just can’t stop making videos (his 2015 Here in My Garage advertisement racked up 67 million views and forced viewers to face their own lack of Lamborghinis). Online marketing has incontestable influence: the steady stream of advertisements in and around our favorite sites diverts our attention and drives our consumption behavior, effects which we do not always welcome.

Story by Hugh Preas '18

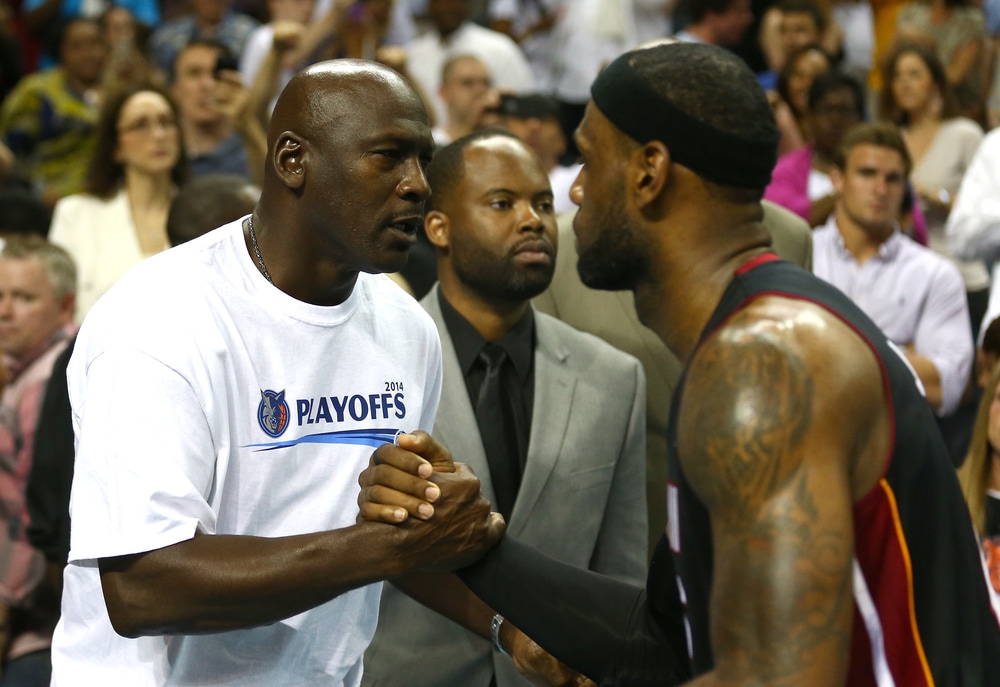

Personally, I side with Jordan when it comes to this debate, but James still has plenty of time left in his career to prove me wrong.

Story by Griffin Shapiro '18  Around this time every year, in the aftermath of the NCAA March Madness Tournament, one often hears the same question repeated by basketball super fans and casual observers alike: Why don’t these players get paid? Everyone else involved in the tournament gets paid for his role in the event, from the coaches to the broadcasters to the colleges whose teams qualify for the tournament. The NCAA itself has a 14-year, $10.8 billion deal with CBS Sports and Turner Broadcasting for the rights to televise the tournament. With so much money changing hands as college basketball becomes a larger and larger business, it’s easy to think that “amatuer” college athletes who play the most important role in the games are exploited by the system. So why don’t the players get paid?

Story by Suzan Michalski '18 The search for truth has become a top priority for many. During the 2016 presidential elections, the email scandal involving Hillary Clinton inevitably placed the issue of “truth” at the center of the debate between the two opponents. On social media and in the news, we constantly hear journalists and media figures calling on the American public to combat Trump’s ideology with facts. During the Academy Awards, the New York Times released a short advertisement titled, “The Truth,” which concluded with the statement that "the truth is more important now than ever." With all this discussion about finding the truth, we must inevitably ask ourselves: what is truth?

Story by John Klingler '18

|