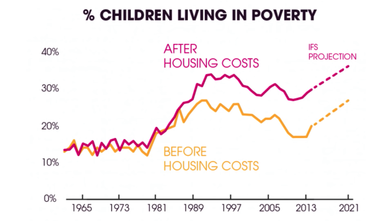

Henry Brown '23 Read any headline, and it will seem as though the world is headed towards imminent disaster. Climate change threatens to displace billions throughout the next century. Power-hungry authoritarian regimes threaten peace and the democratic will. Poverty is skyrocketing, Americans are getting sick, and long-term economic prosperity is uncertain. And yet, there is one solution that can solve these problems. It can restore our nation’s economic prowess, placing the free world in a unique position to stop the spread of autocratic regimes. It can boost our public health, safety, and wellbeing. It can allow us to redirect our political focus away from the petty battles of cancel culture and towards art, science, and galactic exploration. It doesn’t require a multi-trillion dollar bill. In fact, it costs the government nothing. And it is so simple and easy to execute: build more houses. Over the past few decades, home prices in the United States have skyrocketed, especially in cities and their suburbs. After the Recession of 1981, Americans began to see housing as not a commodity, but as an investment. Homeowners now prioritize maintaining or increasing home prices by stopping new developments (they are called NIMBYs, which stands for “Not In My Backyard”). As the country’s population inevitably rises, so does demand for housing. The lack of new supply may be great for homeowners’ portfolios, it is not great for the rest of America. In 2015, around forty percent of all American renters were “rent burdened” (i.e. they pay more than thirty percent of income on rent), and this figure increased by nearly ten percent from 2001. Without access to cheap housing, these individuals increasingly cannot spend their money in other areas of our consumer-centered economy—the income simply ends up in the pockets of landlords. Other data suggest that poverty could be reduced by twenty-five percent—and child poverty by fifty percent—if housing was simply cheaper. However, before 1980, poverty was virtually unaffected by house prices, largely because homes were so widely available. During the thirty years after World War II—often dubbed the Golden Age of capitalism—over thirty percent more houses were constructed each year in the US compared to today. With such high supply, prices were low enough that a father making the median salary could comfortably raise a family of five in a middle-class home. Today, two parents making median income can barely raise one child, if any, in these homes (e.g. Californians making less than $140,000/year qualify for government assistance to pay for rent or mortgage). In the European Union, only one nation has decreasing homeless rates: Finland. Why? Because they permanently house homeless people. Finland still provides all of the resources to these individuals that other nations do, but with homes to ground themselves economically, these people do not need them as extensively. As such, the government has been able to save money with this approach (for example, there is only one homeless shelter in Helsinki, the capital city). If this approach was used nationwide in the United States, taxpayers would see up to a sixty-two dollar tax cut. This strategy does not only work in the socialist utopia that is Finland. Mississippi, the nation’s most impoverished state, has adopted this strategy as well and boasts the nation’s lowest homelessness rate, at just 3.7 individuals per ten thousand. California’s, for example, is over thirteen times higher than Mississippi’s. Even the next lowest, Alabama, has about two times the number of individuals, despite similar economies. Building more homes is better for the environment, too, especially when they are high-density and transit oriented. Today, American suburbs are terribly detrimental to the environment. Per household, they pollute up to eighty percent more carbon than cities and use vastly more water. Suburbanites often spend over half an hour commuting and their large homes and lawns require much more electricity and water. Compare that to city dwellers, who walk or take the subway to work. Plus, they can use city parks without the burden of mowing their grass. Of course, white-picket-fence suburbs are uniquely American—they’re the American Dream, right?—so they should by no means “disappear” for environmental reasons. Yet, the problem with housing in America is that Americans often have no choice but to embrace this lifestyle. In California—the entire state is one big suburb—residents are all but forced to reside in a single-family home because… that is the only option (just 17% of CA housing has more than nine units). New York City, on the other hand, does provide a variety of urban options—condominiums, apartments, townhouses—but they are astronomically expensive. This again forces people out of the city into the suburbs, far away from their workplaces. This lack of choice has negative repercussions on America’s health. In the Netherlands, a study found that living in mixed-use development (i.e. apartments above shops) reduced obesity by 8.3%. Another study found that living near parks cut it by 8.4%. Plus, exercise and nature tend to help one’s mental health and reduce feelings of isolation. Yet, most American suburbs end up with the opposite result. A car is a necessity to travel anywhere (those with a long commute are 33% more likely to be depressed and 21% more likely to be obese) and the only green space is often one’s front lawn. Europeans may eat smaller portion sizes than Americans, but they also walk it off. No wonder Europe is beating us in that metric. There are still more reasons to build more houses. It is estimated that the American economy would be seventy-six percent larger if this housing crisis had never happened. That's a GDP of thirty-six trillion dollars. Other economists predicted that if just New York, San Jose, and San Francisco permitted the construction of many more homes, the median US salary would rise by at least $8,700, even for those outside of those cities, because landlords would cease negating the productivity of American workers (sources below). By blocking Americans from living and working in cities, the housing crisis stops the economy from peak performance. It inhibits innovation, it halts creativity, and it slows down our nation’s growth. Moreover, the housing crisis has also contributed to the rise of anti-status-quo extremism in Western society. Young people, unable to afford the quality of life that their parents and grandparents could at their age, turn to progressive candidates further left than most Democrats (or nation's respective liberal party) and protest often for a slew of economic and social reforms. Meanwhile, older voters, comfortable in their expensive, suburban homes, cannot sympathize with the young and often believe them to be “radical” and “entitled.” They become reactionary and swing to the right, more right than traditional conservative politics. Just look at France, a nation also plagued with a housing crisis: in their most recent election, the second and third most popular candidates were not from the established liberal and conservative parties, but Marine Le Pen, who wants to stop all immigration, and Jean-Luc Mélénchon, who supports a 100% income tax on those making over €360,000. Even Sinn Féin—Northern Ireland’s separatist party in a territory designed to prevent their victory—won the most recent election in large part due to youth outrage over high home prices. There are still more reasons to build more houses. In the United Kingdom, the average fertility rate (i.e. average number of births per woman) decreases five percent with every ten percent increase in rent. While much of the developing world reckons with overpopulation, in developed nations like the United States, the replacement rate is less than two. This could wreak havoc thirty years down the road (as it is today in Japan), because we may not have enough people to support the elderly in the economy. So, how can the United States build more homes? The answer is not a multi-trillion dollar Works Progress Administration 2.0 or a massive expansion of federal power. It is deregulation. Yes, that’s right, deregulation. As with most problems in the United States, single-family housing is so widespread because of a Supreme Court decision: Village of Euclid v. Ambler. In the 1920s, the city of Euclid, a suburb of the rapidly expanding Cleveland, wanted to keep African American workers out of the town, so they mandated that developers could only construct single-family housing—the most expensive type. The Ambler Realty Co. argued that this law violated its Fourteenth Amendment rights to the property it owned, but the Supreme Court upheld Euclid’s jurisdiction. This ruling triggered countless municipalities to enact laws to only build high-priced single-family homes, thus preventing minorities from moving in and cementing the white influence in the area. Today, most zoning laws still remain and make it illegal to build cheap, multi-family housing in certain areas. Developers are desperate to compete with one another to build cheap housing for Americans—this is what capitalism is designed to do. Some companies may even be willing to go as far as the Supreme Court, just like Ambler. Yet, city and state governments stand in the way of the free market for the sake of the NIMBY. Take Houston, TX. The city eliminated most of its zoning requirements, and as such, its housing prices are twenty percent cheaper than average. Of course, the city is an urban planner’s worst nightmare, but it remains one of the United States’s most powerful economic centers. If Americans are serious about tackling the housing crisis, zoning requirements must be reduced, or at least reformed in a way that promotes more development. Cities concerned about environmental impact can require new developments to follow green standards. Those worried about a building not fitting in architecturally can regulate the design or put several designs up for a neighborhood vote. And if private investment slows down, the government can enter the game, either funding subsidies or building its own houses to further lower prices. We just need to build more houses. Right now, it seems everything is at stake. Our planet is at stake, our health is at stake, and our economic prosperity is at stake. Yet, we have a solution that is so mind-bogglingly simple, so all-encompassing that it is shocking we have not implemented it. Our nation has potential—sixteen trillion dollars worth—held back due to burdensome regulations. We can once again achieve a golden age of capitalism—one more inclusive for all Americans. We can be the “city on a hill” in terms of health, happiness, and environmental safety. We can focus not on petty infighting, but on art, science, and exploration. It will be a tough fight, but a worthy fight. Our nation has potential. So let’s liberate it. Main Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4ZxzBcxB7Zc&t=1538s Other Sources: https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2018/04/rent-burden_report_v2.pdf https://www.statista.com/statistics/727847/homelessness-rate-in-the-us-by-state/ https://www.infoplease.com/us/census/california/housing-statistics https://www.infoplease.com/us/census/new-york/housing-statistics https://www.bestplaces.net/cost_of_living/city/texas/houston https://pastebin.com/f6ZE2Vf4 https://www.economist.com/britain/2015/09/24/through-the-roof https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/mac.20170388 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nUFZ1_fC3Kw https://www.statista.com/statistics/377830/number-of-houses-built-usa/

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

|